The Soldier and the Jungle: The Brazilian Army and its narratives for the Amazonian border

by Pedro Augusto P. Francisco

⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄

In November 2017, between the 5th and the 13th, the Brazilian Army held a huge military exercise called Amazonlog17: a multinational inter-agency logistics and humanitarian exercise in the city of Tabatinga, in the middle of the Amazon Forest, located right at the triple-border between Brazil, Colombia and Peru. The idea was to build a multinational military base in an environment considered to be hostile and challenging, in order to support civilians and military in a remote region. The Amazon Forest has a strong symbolic power for the Brazilian Army. It is at the same time a stage on which to excel and a character in a complex narrative: a thing to be saved and protected, but dangerous and indomitable. For all of these complexities, the Amazon Forest works as source of power for the military, one of their raison d’être.

As an anthropologist working with borders since 2012, I was interested in understanding if the so-called North Triple-border had any role in this imaginary. Since Brazil is a country with very little involvement in armed conflicts and, at the same time, has an immense land border in the Amazon region, with almost ten thousand kilometers, the North Triple-border is the ideal mobilizer of a force that justifies its existence on a sense of threat to national sovereignty. I saw Amazonlog17 as a perfect opportunity to see first-hand how the Army would use that particular border in its discourses and practices during the exercise, so I made a request to the Amazonlog17 Command to participate as a National Observer.

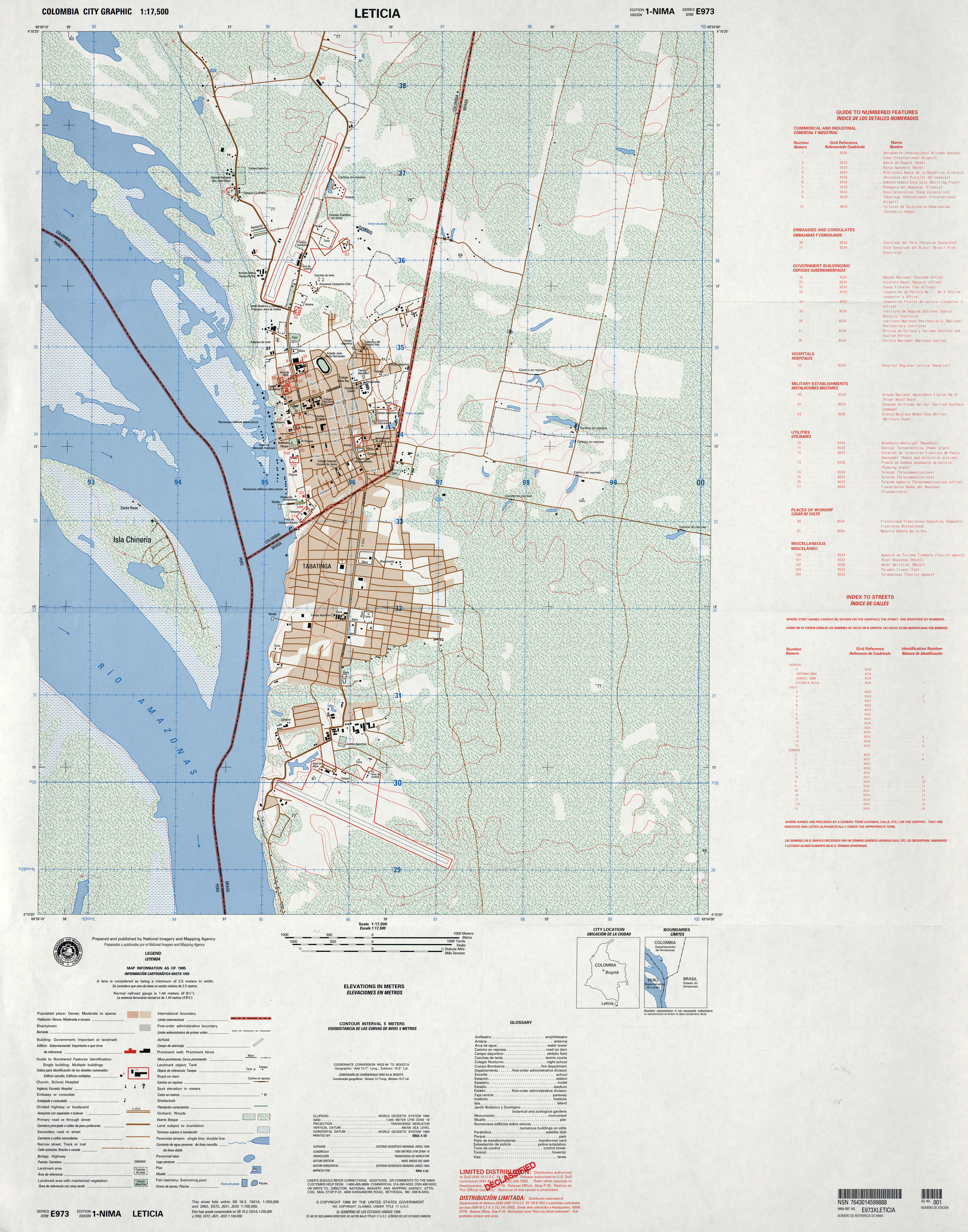

Map of the North Triple-border, showing both the cities of Tabatinga – Brazil and Letícia – Colombia, as well as part of Peru.

The Amazon as the Army raison d’être

In the course of Amazonlog17, observers had to follow a fixed schedule. They put me together with the other 37 international military observers, members of the 22 friendly nations invited to observe the exercise. During those 10 days in a military base in the middle of the Amazon Forest we shared meals, rooms and activities. I was sharing a room with colonels of a foreign Latin American army. One evening, while we were having our regular chats, they said how impressed they were with the size of the exercise, which surely had cost a significant amount of the Brazilian Army budget. Their true question, however, was “is it worth it?” Then, one of the colonels asked me, “What does the Amazon mean for the regular Brazilian? Does it mean something big and important enough in order to justify this whole circus that the Army is making?”

Even though I had never thought about that question before, it wasn’t difficult to answer. For most Brazilians, especially the ones that were raised and lived in the southern and more populous regions of the country, the Amazon was a distant, savage and exotic place. According to journalist José Arbex Jr (2005: 21), the Brazilian imaginary still pictures the Amazon in the same way that Portuguese colonizers saw the whole country during the 16th century: a pristine place, at the same time full of richness but inhabited by indomitable beasts and strange people.

In the Brazilian Army imaginary, however, the Amazon Forest occupies a completely different place. In 1985, the Brazilian Armed Forces were finally subordinated to civilian power. Since then, they have been struggling to achieve a clearly defined social role, especially in the eyes of the country’s middle and upper classes. They suffered a loss of prestige due to the lingering memory of their role during the military government from the 1960s to the 1980s, and the fact that the country is not involved in any major conflict. Against this backdrop, the Brazilian Army has been trying to find its role through the growing importance of protecting national sovereignty, especially in the Amazon region (Castro 2012: 175).

Ten years after its subordination, in 1995, General Zenildo Lucena, Minister of the Army at the time, affirmed during a talk at Fort Leavenworth that defending the Amazon forest was “Brazil’s manifest destiny.” To reinforce this narrative, the Army has been inventing a tradition stating that its presence in the Amazon started at the beginning of the 17th century, fighting for the nation’s sovereignty in the region since then – despite the fact that there wasn’t a country called “Brazil” at that time. In order to make sense, the narrative also needed to introduce some enemies, in which the Amazon border had a constitutive importance, such as the international drug trafficking (Castro and Souza 2012: 177-178).

In order to understand the importance of an exercise such as Amazonlog17, in lieu of asking what the Amazon means to a regular Brazilian, one should ask its importance to the Brazilian Army. The next questions to ask are the ones regarding the role the Amazonian border plays in this Army narrative, and how Amazonlog17 fits into it.

Three narratives for the same border

Amazonlog17 was huge. The Brazilian Army managed to build an entire functional base from scratch, able to host about 2000 people. In addition to the military observers, the exercise gathered together not only members of the Army, but also troops from Peru, Colombia and the United States, as well as people from 22 governmental agencies. Since the concept of a war exercise at the border would raise a negative reaction from the Brazilian public – considering the presence of foreign troops on national soil – the Army decided to perform it in a different way. The idea was to test the Brazilian Army’s logistics mobilization capacities in the occurrence of a humanitarian crisis, along with the necessity to coordinate an integrated response with governmental agencies and the Armed Forces of bordering countries.

Preparation for Amazonlog17 inauguration ceremony.

In the words of four-star General Theophilo, Logistics Commander of the Brazilian Army and highest officer in charge of Amazonlog17, “it would be easy to do the exercise in cities like Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo or even Manaus” – capital city of the state of Amazonas. These are big cities, well served by roads and connections with the rest of the country. The Army logistics capacities would only be truly put to proof by doing the exercise in a remote area, such as in the heart of the Amazon Forest, right at the border with Peru and Colombia.

It is interesting to see the border at this narrative. Here, the Amazonian border is a stage. Not only for the “theater of operations,” but also for the Army’s public performance during the exercise, aimed to demonstrate its supremacy and power in that scenario. One can argue that other institutions are capable of operating at the Amazonian Border, such as the Federal Police or the National Civil Defense. Nevertheless, Amazonlog17 was the Brazilian Army’s opportunity to show it is the only one with the capacity to articulate 22 government agencies and mobilize 2000 people in a short time. More than that, it was an exhibition of power in the face of foreign Armed Forces and international observers. The border was a place to show how the Brazilian Army excelled in the Amazon Region.

The border is also a place of direct contact and constant movement of people and goods between three different nations. There is only a street separating Tabatinga from the city of Letícia, in Colombia, with no border control and only a sign showing one is leaving a country and entering another. Once one crosses this street, one can see and hear that the language has suddenly changed from Portuguese to Spanish. On the Peruvian side of the border, there is the town of Santa Maria de Yavarí, located in a small island in the Amazon River. All this movement enabled by close contact and nonexistence of border control gives the impression that the North Triple-border is a place of friendship between countries. There, despite the language differences, people from these three countries share a common urban life and an Amazonian identity. This is reflected in the name of Tabatinga’s main avenue – the Friendship Avenue – that starts at Tabatinga International Airport and ends at the city center in Letícia.

During Amazonlog17, the Army explored this image. Doing a humanitarian exercise together with the Peruvian and Colombian Army was an act of friendship, one that exists only because of the border. It was a way of showing that the three countries shared the same problems and together should find its solutions. Regarding this aspect, the Armies of Brazil, Peru and Colombia tried to show that borders do not need to divide, but can aggregate. They were, after all, institutions charged with the responsibility to protect and defend the Amazon, which goes beyond borders.

The last aspect associated with the Amazonian border during Amazonlog17 was as a source of problems. Despite being isolated in the middle of the jungle, distant from major urban centers and accessible only by river and air, Tabatinga is a big city by Amazonian standards. It is among the 10 biggest cities of the Brazilian state of Amazonas, with a population of about 60 thousand people. A place that connects three countries with navigable rivers, which allows people and objects to arrive in the ocean would turn out to be one of the main geographical corridors for the circulation of goods in the continent. In addition, it is natural that this corridor would allow the circulation of illegal goods. As a result, Tabatinga is a violent city, one of the few among the entire Brazilian border where transnational crimes have a straight connection to local public security issues (Neves et al. 2016: 27).

Transnational crime is one of the key concepts to understand the Army presence and recent work at the Amazonian border. In Brazil, this concept refers mainly to international drug trafficking, human trafficking and wildlife smuggling. Insecurity at the border is directly associated with these illegal commercial circuits and, furthermore, there is a narrative connecting public security problems at Brazil’s main urban centers with them. It is through the urgency imposed by the need to control these practices that public and national security have been promoted to be the main focus of public policy concerned with the Amazonian border (Hirata 2015: 30).

Despite the focus on logistics and humanitarian issues at the border, the importance of fighting transnational crime was mentioned during the presentations made at the beginning of Amazonlog17 activities. When talking to senior officers who were responsible for the exercise, they always said that people who lived at the Triple-border were victims of the dynamics of transnational crime, so that any humanitarian action should include its repression. General Theophilo said that one of the objectives of Amazonlog17 was to strengthen and increase surveillance in the region, in order to fight transnational crimes. According to him, these crimes affected not only people at the border but also those in Brazil’s major urban areas. Thus, the Amazonian border was one of the major public security issues in the country and the Brazilian Army, entrusted with the task of protecting the Amazon, was the most qualified institution to tackle it. Amazonlog17 was an opportunity to show the world how the Army has the strength to fight this problem, justifying its existence in the eyes of Brazil.

The Amazon and its border as a single narrative

At Amazonlog17, I could see how the North Triple-border has different and apparently contradictory roles in the Brazilian Army’s narrative. It was seen, at the same time, as a stage to perform its power, a place to engage with its friends, and a source of Brazil’s public security problems. One can conceive borders as a geopolitical concept. They are imaginary lines on the ground, instruments of governmental power used to affirm a state’s sovereignty over a certain territory. However, borders are more than that. They are cultural products with the capacity to create identities and stories, objects with material and immaterial natures that can be sewn by different narratives. Its fluidity permits the representation of the Amazonian border as a place where nations that touch each other can be friends, but contradictorily, it is this same proximity enabling the circulation of people and goods which is the reason behind its role as a security problem.

The Army’s narratives for the Amazonian border are intertwined with its broader narrative for the Amazon forest. It is dangerous and marvelous. It must be saved and protected. It is the reason for a soldier’s existence, where they are trained and must take action. There, in the middle of the jungle, the border dissolves and mixes with people, stories, trees, rivers and animals, forming a single and immense entity.

⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄⁄

All the works cited in this essay were originally published in Portuguese. In order to allow international readers to understand what kind of works I used, I am providing a translated title right after the original.

Arbex Jr., José (2005) “Terra sem povo, crime sem castigo: Pouco ou nada sabemos sobre a Amazônia”, Amazônia Revelada. Brasília: CNPq, pp. 21-66.

(ENG: “Land without people, crime without punishment: we know little or nothing about the Amazon”, Amazon Revealed).

Castro, Celso (2012) “Comemorando a ‘Revolução’ de 1964: a memória histórica dos militares brasileiros”, Exército e Nação: estudos sobre a História do Exército Brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: FGV Editora, pp. 143-175.

(ENG: “Celebrating the ‘Revolution’ of 1964: Brazilian military’s historical memory”, Army and Nation: studies on the Brazlian Army’s History).

Castro, Celso and de Souza, Adriana Barreto (2012) “A Defesa Militar da Amazônia: entre história e memória”, Exército e Nação: estudos sobre a História do Exército Brasileiro. Rio de Janeiro: FGV Editora, pp. 178-228.

(ENG: “The Amazon’s Military Defense”, Army and Nation: studies on the Brazlian Army’s History).

Hirata, Daniel (2015) “Segurança Pública e Fronteiras: Apontamentos a partir do Arco Norte”, Ciência e Cultura, 67: 30-34.

(ENG: “Public Security and Borders: notes from the Northern Arch”, Science and Culture).

Neves, Alex Jorge das et al. (2016) Segurança Pública nas Fronteiras: Sumário Executivo. Brasil: Ministério da Justiça, Secretaria Nacional de Segurança Pública.

(ENG: Public Security at the Borders: Executive Summary).